By Peter Pavarini

Nature doesn’t play it safe. It continuously reshuffles the deck, selects winners over losers, destroys the weak and replaces them with the strong. Operating within a closed system, nature perpetually regenerates itself using random events to its advantage, rather than suffering permanent harm because of them.

Until recently, humans generally functioned in conformity with these principles. Whether we liked it or not, we recognized we couldn’t guard against every calamity and did the best we could to mitigate the risk that might occasionally claim some of us. That seems to have changed, however, in just the past two or three generations. Instead of nature’s utilitarian approach, we’ve embraced the utopian ideal that, through science, technology and social engineering, humans no longer need to accept the uncertain fate of our ancestors.

An 85 Percent Drop in Success?

Before you dismiss this view of today’s culture, consider the following. Between 1800 and 1985, the number of times the word “success” appeared in a very large sampling of publications[i] remained remarkably constant. But by 2020, the appearance of that word had fallen 85 percent. Such a precipitous drop in just 35 years can’t be explained by the natural evolution of language, but instead must be seen as indicative of a fundamental shift in cultural values.[ii]

Dozens of studies conducted in recent years have compared the five generations of Americans currently working in our economy. For sake of simplicity, I’ll focus on just two of them: Baby Boomers (born 1946-1964) and Millennials (born 1981-2000).

Whereas, Baby Boomers are generally characterized as self-confident, competitive and ambitious, Millennials are said to be fiercely independent, individualistic, and self-absorbed. Boomers place great importance on achieving success and often express that in monetary terms. In contrast, Millennials (primarily the children of Boomers) are motivated by achieving “balance” in their lives and look to their peers – not their elders- for direction and help in achieving that goal. While the obsessive ambition of many Boomers gave rise to the term “workaholism”, Millennials now see work as no more than a “gig” – something you only do to get paid.

Focusing on Risk Avoidance, Safety and Security

Against this generational backdrop, it’s easy to see why American society has moved away from seeking success at all costs and instead has focused on risk avoidance, safety and security. Increasingly, we’ve lost the capacity to do things – big and small- before we completely understand the consequences of doing them. Instead of taking risks, historically the catalyst for human advancement, we now seem more concerned about controlling the volatility of random events – both natural and manmade. Is there a better explanation for the morbid fear so many young people seem to have about climate change – something that has been the norm, not the exception, throughout the Earth’s 4.6-billion-year history?

What happens to a society when it values other worthy goals like ending inequality or promoting social justice over success? What replaces the pioneer spirit, the “can-do” attitude that propelled our nation’s development for over 200 years?

In the past, almost all discovery and innovation derived from a willingness to tinker with the status quo and bear some risk doing so. Risk-takers were generally admired, not only because they exposed themselves to the downside of their actions, but also because they frequently did so for the benefit of others. We considered them heroes because they had some “skin in the game”.

Lessons From the U.S. Space Program

Having recently visited the Kennedy Space Center, I came away more impressed by the astronauts who are memorialized there than by any of the equipment they rode into space. Using technologies primitive by today’s standards, they accepted the very real risk of death, and indeed several sacrificed their lives in pursuit of the age-old dream of space flight.

As President John F. Kennedy said early in the U.S. space program:

“We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win….”[iii]

A New Class of Non-Risk-Takers

Never in recorded history have so many non-risk-takers been given so much control over matters of utmost importance. In the words of Nassim Nicholas Taled, the author of Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder[iv]:

“[Today] we are witnessing the rise of a new class of inverse heroes, that is, bureaucrats, bankers, Davos [attendees], and academics with too much power and no real downside and/or accountability. They game the system while citizens pay the price.”[v]

The global response to the COVID-19 pandemic is just one recent illustration of this point. Although the origin of the disease remains hotly debated and a complete cost/benefit analysis of the public health measures taken still needs to be done, a few things are abundantly clear. For one, the medical establishment’s skepticism about the human body’s natural ability to heal itself undermined whatever we did or didn’t do to combat the pandemic. How might things have worked out had doctors been allowed to use traditional disease-containment measures instead of relying upon an experimental pseudo-vaccine?

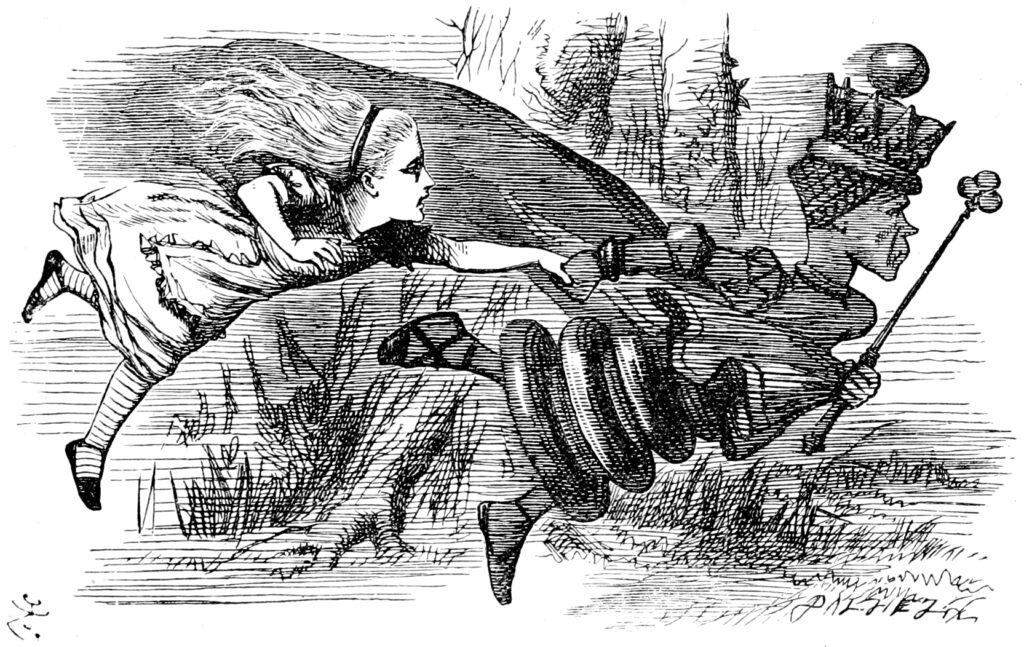

Running in Place Just to Keep Up

As is true with most problems, simple solutions often turn out to be more effective than complex ones. Doing less often beats doing more. Despite all the modern advances in science and technology, Americans appear to be experiencing what the Red Queen explained to Alice in Lewis Carrol’s Alice in Wonderland:

“Now, here [in Wonderland] …it takes all the running you can do to keep in the same place. If you want to get somewhere else, you must run at least twice as fast as that!”

Why do so many of us feel continuously anxious and exhausted by the pressures of modern life despite having the benefit of so many high-tech labor-saving devices?

In his seminal work, The Collapse of Complex Societies[vi], anthropological scholar Joseph A. Tainter observed:

“Human history as a whole has been characterized by a seemingly inexorable trend toward higher levels of complexity, specialization and sociopolitical control.”

While reaping the benefits of a sophisticated, high-tech society is not itself bad, it’s not a substitute for cultivating creative talent and testing the limits of human potential.

The two most notable characteristics of a complex society are its inherent inequality and its heterogeneity[vii]. Once humans abandoned the simplicity of the hunter-gatherer lifestyle, which had been the norm for most of human history, members of a given people group were quickly sorted by rank and had unequal access to goods and resources. Likewise, as class replaced kinship as the dominant mechanism for organizing a society, the social order became increasingly dependent upon centralization and governmental control. This is true without regard to the form of government chosen by the people group or by its political ideology.

Complexity is a House of Cards

Although some level of complexity is the hallmark of every civilized society, accepting greater levels of interdependent specialization only makes sense when that continues to enhance the society’s overall standard of living. Beyond that, it become a burden that can bring down the entire “house of cards”.

The reason for this is simple. Complex societies are far more costly to maintain than simple ones. Once the cost of being a member of particular society exceeds the perceived benefit to the individual, the benign forces which held the population together will no longer be enough to maintain the social order. Authoritarian forces rush in to take their place.

Harbingers of Collapse

Russian author Dmitry Orlov has identified five ways people become aware that their society may be headed toward collapse. His analysis, while admittedly bleak, is instructive to people like myself who aren’t about to give up on American society.

- Financial. Faith in business as usual becomes lost. Uncertainty about the future makes it harder to measure risk and value assets. Banks become insolvent, savings are wiped out, and access to capital is lost.

- Commercial. Faith in the marketplace’s ability to sort things out is lost. Money is devalued[viii], commodities become scarce and are hoarded, productivity declines[ix] and supply chains break down.

- Political. Faith in the government is lost. Once official efforts to mitigate the loss of access to necessities fail, the political establishment loses its legitimacy[x].

- Social. Faith that other people will take care of you is lost. Local institutions like schools[xi], charities and community organizations run out of resources or fail because of internal conflict.

- Cultural. Faith in humanity is lost. People lose their capacity for kindness, generosity, honesty, compassion, etc. Family groups disband and individuals compete for remaining resources.[xii]

Each of the foregoing societal dimensions rests upon a belief that the order of things will remain stable through the next generation or two. When that level of trust is compromised by specific events (e.g., wars, natural disasters) or changes in social norms (e.g., falling birthrates, increased violence), a society can no longer rest upon its past accomplishments. It must rely upon its best and brightest members who are hopefully in positions of authority or influence to find new solutions to the society’s problems.

What Our Best and Brightest Should Be Doing with Their Free Time

Finding solutions becomes extremely difficult when those who previously had devoted their underutilized capacities and resources to problem-solving are now using their free time[xiii] mostly for leisure, entertainment and virtual experiences (e.g., “screen time”).

Dumbing down what it means to be “successful” in today’s America is perhaps the best predictor of whether our society will endure for another 200 plus years. If we continue to choose safety and comfort over doing JFK’s “hard things”, if we reject applying high standards because some in our society might not measure up to them, or if we replace thousands of years of cultural norms because we think no one is watching, then we must be prepared for the harsh reality of what it means to be unsuccessful.

[i] Based upon a Google tool that measures the frequency of a word’s usage over the years across a sample of 8 million books.

[ii] Mike Donghia, “Why Success Fell Out of Fashion and Why It Matters”, The Epoch Times, March 8-14, 2023.

[iii] President John F. Kennedy, Address at Rice University on the Nation’s Space Effort, September 12, 1962, www.jfklibrary.org

[iv] Random House (2012) at p. 6.

[v] It has been reported that the net worth of America’s 686 billionaires increased $1 trillion during 2020, the first year of the pandemic, while the rest of the population suffered a major financial setback that has continued into 2023. By comparison, the economic impact of the last global pandemic – the Spanish Flu of 1918-1919 – was relatively short-lived and was followed by a decade of widespread prosperity.

[vi] Cambridge University Press (1988) at p. 3.

[vii] Ironically, these are the two characteristics of Western civilization most frequently attacked by reformers.

[viii] During Nero’s reign as emperor of Rome around 54 A.D., the denarius was 91.8% silver. By the reign of Septimus Severus around 193 A.D., the amount of silver in that coin had dropped to 58.3%.

[ix] U.S healthcare, while still producing better outcomes than most other systems, has declined in productivity since the 1960s. Even with the benefit of numerous medical advances, healthcare providers don’t deliver as much care as they did a few decades ago.

[x] Larger, more specialized bureaucracies are indicative of political collapse. Increased regulation and enforcement mechanisms are required to implement governmental fiat. This in turn requires greater taxation, further undercutting public support for centralized decision making.

[xi] During the decline of the Roman Empire, there was a pronounced decline in literacy and mathematical education. As now being witnessed in American public education, notwithstanding never-ending increases in spending the past few decades, academic achievement in public has been in a steep decline.

[xii] Dmitry Orlov, Reinventing Collapse: The Soviet Experience and American Prospects, New Society Publishers (2011).

[xiii] In the past, the most capable members of a society devoted their free time to learning, discovery and cultural enrichment. In the Neolithic Era, this gave rise to pursuits like writing, philosophy and the arts – without which modern society would never have existed.

Be First to Comment