By Peter Pavarini

“Never ascribe to malice that which is adequately explained by incompetence.”

-Robert J. Hanlon[i]

In a hyper-politicized world of conspiracy theories and memes, it’s easy to confuse an anomalous event with what it really is – a screw-up, plain and simple. Platitudes like “that should never happen” or “there’s no room in America for such behavior” don’t absolve the incompetence that is now endemic in society.

I was in high school when researchers Laurence Peter and Raymond Hull coined the phrase “the Peter Principle”.[ii] Even though their eponymous book was meant as a satire, it quickly became recognized as a serious critique of personal performance in the modern era. Over the past 55 years, the Peter Principle has served as a clichéd way to explain the high level of ineptitude found in most hierarchal organizations.

We’re All Born Ignorant

As Ben Franklin wisely pointed out, “we are all born ignorant, but one must work hard to remain stupid.”[iii] Since the introduction of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in 1440 and the common school movement founded by Horace Mann in the 19th Century, ordinary people have had little reason not to become at least functionally literate, allowing them to participate fully in society. The developed world’s rapid industrialization over the past 200 years should be credited as much to the growth of an educated workforce as to any technological achievement.

Nevertheless, the human species remains prone to error. The first zero-defect person has yet to be born. Even with the coming revolution in artificial intelligence, it’s unlikely that AI will ever be a match for natural stupidity.

That’s especially true when the government is involved.

Gerald Celente, American business consultant and publisher of the Trends Journal, has said:

“The greatest fears that governments have are freedom of speech and exposing the corruptness, the ineptitude, and the double dealing going on that they don’t want the public knowing about.”

Similarly, the bestselling author Jim Collins[iv] has explained the problem this way:

“The purpose of a bureaucracy is to compensate for incompetence and lack of discipline- problems that largely go away if you have the right people in the first place”.

Considering how ill-informed and gullible the average person is, it’s frightening to think that half of the population is more ignorant than that.[v] Imagine how many important things are done each day by people who are not up to the job. That might only cause minor inconvenience when it involves getting your order right at a fast-food restaurant, but when it concerns the building of a $125 million Boeing 737 Max 8, it could have disastrous consequences. And when the error or deficiency affects the education of a nation’s children, it could ripple through a population for generations.

Applying the Peter Principle to Today

Beginning with the premise that over time all human systems drift toward mediocrity, consider what happens when you add a well-intended but disruptive social engineering program like Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (“DEI”) to the mix. Based upon the highly debatable proposition that all people are equal in ability and therefore entitled to share equally in society’s accomplishments, DEI has become the 21st century’s version of the Peter Principle.

After failing to raise the standard of living of society’s least successful members by other means, America has defaulted to a standardless system which slots people into positions of responsibility based on factors over which they have no control. Gender, racial and other forms of demographic diversity may be admirable in themselves, but the pursuit of such utopian goals should never be done at the expense of millennia of human achievement.

Like many other social reforms, dramatic change often begins in the public sector. I spent four years working in the federal government at the start of my career (well before the era of DEI) and even then, I noticed significant differences between the competency of civil servants and those in the private sector. Since that time, the number of government employees has nearly doubled while the US population has increased by less than 50%.[vi] Leaving aside the question of how much government Americans need, there’s still a legitimate question about the caliber of the people filling those jobs.

Nothing we expect the government to do is more important than protecting the lives of our citizens. Whether that involves fighting foreign wars, defending our borders, protecting our leaders, eliminating communicable disease, or preserving law and order, no American honestly wants the “B Team” assigned to those tasks. When the World Trade Center was attacked in 2001, we counted on those with the highest levels of skill and courage to run into burning buildings and evacuate trapped people. No one cared about the skin color of the firefighter or the office worker who was saved.

Finding and Cultivating Leaders

Finding and cultivating competent leadership is hard, both in the public and private sectors. As I discussed in another blog[vii], exceptional leadership is so rare that it must be nurtured and rewarded wherever it appears. The greatest impediment to raising up effective leaders is the power of stupid people functioning in large groups. Not only do stupid, inept people have a numerical advantage, but as Mark Twain once said, “they will drag you down to their level and then beat you with experience.”[viii] Touchy mediocre people feel immediately threatened whenever someone’s work proves to be better than their own.

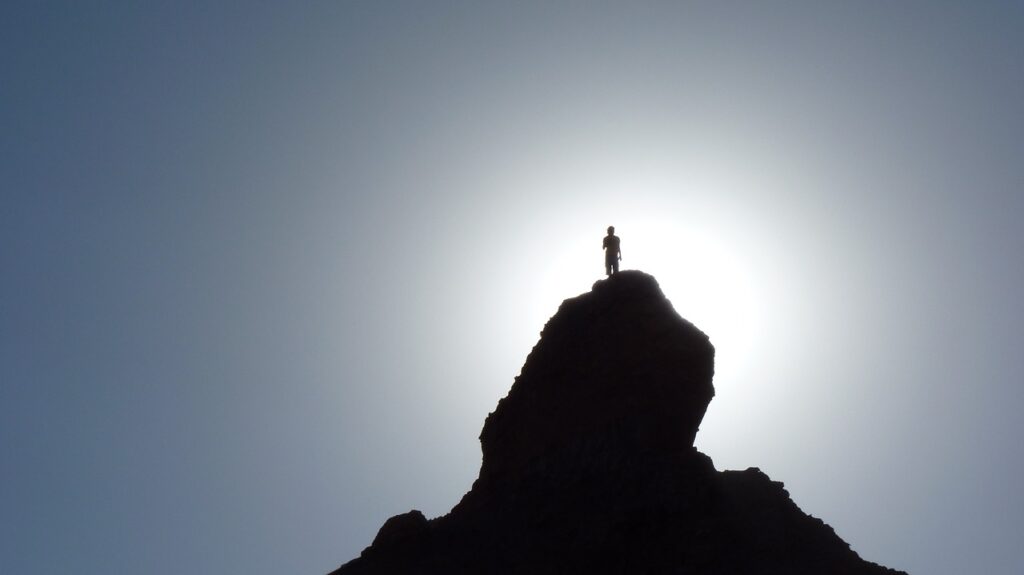

I’ve also blogged recently about heroism.[ix] During times of political and economic instability, such as now, the need for role models and heroes increases exponentially. Human nature appears to be at its best only after it is subjected to the trials of hardship, discipline and the acceptance of risk. In a society obsessed with safety and fairness, the value place on taking risk has been greatly diminished; however, we instinctively remain drawn to those who willingly subject themselves to great danger. We admire them not simply because they are so few, but also because we can’t imagine doing what they do when under attack. This innate attraction to displays of courage is powerful and weighs heavily in our choice of leaders.

Recognizing Exceptional Achievement

Consequently, despite all of today’s DEI zealotry, it’s not surprising when a spontaneous demonstration of strength under fire gains the respect of the masses – just as it has since time immemorial. Today’s Peter Principle may have succeeded in conferring status and reward (deserved or not) on a larger cross-section of the public, but it has not replaced our collective desire to recognize and elevate people of exceptional character and ability.

Much has been written about the sense of isolation and exclusion faced by highly successful people. Harvard Business Review has reported that feelings of loneliness plague many CEOs once they take on the top job.[x] After reaching the top level of an organization, it becomes harder for a successful person to socialize with others. Even Albert Einstein remarked how strange it was to be internationally well-known but still feel lonely. Moreover, the higher people climb the organizational ladder, the fewer trusted relationships they have and the more frequent are the attacks on their character.

It’s indeed lonely at the top, but it should also be frightening for anyone who got there on reasons other than merit.

[i] Based upon a centuries-old adage, “Hanlon’s Razor” was popularized by author Robert J. Hanlon.

[ii] Laurence Peter & Raymond Hull, The Peter Principle (William Morrow & Co., 1969). The book was based on research showing that, in seniority-based systems, people are generally promoted to positions beyond their level of competence. The book also demonstrated that most of the actual work done in any organization is accomplished by those individuals who have not yet reached their level of incompetence.

[iv] Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap and Others Don’t, Harper Business (2001).

[v] A one-liner attributed to the late great comic George Carlin.

[vi] See Paul C. Light, The True Size of Government is Nearing a Record High”, Brookings, October 7, 2020.

[vii] The Making of a Philosopher King – alessandrocamp.com, January 7, 2024.

[ix] https://alessandrocamp.com/2023/08/18/we-still-can-be-heroes/

[x] Kati Najipoor-Schutte and Dick Patton, “Survey: 68% of CEOs Admit They Weren’t Fully Prepared for the Job”, Harvard Business Review, July 18, 2018.

Be First to Comment