By Peter Pavarini

In anticipation of humanity’s return to the Moon later this year, I’ve been brushing up on my outdated knowledge of astronomy by reading Timothy Ferris’ Coming of Age in the Milky Way[i]. When this book was first published in 1988, it was considered little more than a layman’s guide to the universe. But, even now, it offers a thoughtful summary of mankind’s quest to understand outer space despite the political and religious roadblocks that stood in the way. Although much of the cosmos is still mysterious, nothing about it perplexes scientists more than the subject of dark matter.

In one of Stephen Hawking’s last works, Unlocking the Universe, the brilliant astrophysicist admitted:

“The missing link in cosmology is the nature of dark matter.”[ii]

The Quest to Understand Dark Matter

In lay terms, dark matter is the invisible glue which holds the universe together. A more precise definition has eluded astronomers and astrophysicists for nearly 100 years.

When American astronomer Edwin Hubble was cataloguing galaxies and other celestial objects during the 1920s, he realized that his mathematical calculations didn’t quite add up. Something invisible was needed to balance his equations.

In 1932, Dutch astronomer Jan Hendrick Oort also noticed that stars were moving faster than his calculations predicted. He coined the term “dark matter” to describe an unidentified form of mass that seemed necessary to explain their velocity.

Not until Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity was applied to this problem was dark matter taken seriously. Astronomers studying star clusters discovered that the light coming from these stellar bodies was being bent by an unseen mass between the observer and the star cluster. Einstein previously predicted that space-time close to a massive object would be distorted causing a noticeable shift in the color of such starlight. But not until this distortion was confirmed by the Hubble space telescope in 1997 was Einstein’s theory verified. An invisible mass 250 times greater than the mass of the star cluster itself “proved” the existence of dark matter.

What Comprises Dark Matter?

So, what exactly is this mysterious stuff? The current definition of dark matter remains rather vague. Most astrophysicists now describe dark matter as a class of subatomic particles which neither reflect nor generate light. Despite its invisibility, dark matter is said to account for as much as 85% of all mass in the universe. How can something only known through indirect clues[iii] be real?

Some say that dark matter is so elusive that human intelligence is not enough to comprehend its true nature. Because of our mental limitations, only through the use of artificial intelligence will its secrets be revealed.

Author Tom Golway recently expresses this as follows:

“AI’s greatest challenge won’t be processing data – it will be accounting for the dark matter of unseen variables that shape our world in unpredictable ways.” [iv]

This has not, however, stopped scientists from speculating about the composition of dark matter.

The leading candidate is a type of subatomic particles amusingly known as “WIMPS” – specifically, weakly interacting massive particles. You may ask: how can anything wimpy be capable of bending light or causing stars to accelerate? At least Superman had Kryptonite.

Other candidates for dark matter are axions (extremely light neutral particles), neutralinos (a heavier form of neutrinos) or photinos (an even heavier form of photons). Got that?

Then again, dark matter may be nothing more than a bunch of extremely tiny particles scattered hither and yon among the stars. Such particles could aggregate into structures, such as the scaffolding that holds galaxies in place. They could even be primordial black holes[v] – immature versions of those massive light-sucking monsters that occupy the center of most galaxies. Lastly, for ardent sci-fi fans, there’s a theory that dark matter is evidence of a parallel universe that has nothing in common with the universe we know and love.

The composition of dark matter is so perplexing that even the mammoth Large Hadron Collider[vi] has been engaged to find an answer. Astronomers have also been sifting through mountains of data generated by the Fermi gamma-ray space telescope[vii] in hopes of finding a clue to unlock this mystery.

In the Absence of Empirical Evidence, Where Should We Look?

Are scientists looking in the right places? If the scientific method requires empirical evidence to support a new theory and none exists, what can be done? Perhaps dark matter only exists in a metaphysical realm not meant to be understood by traditional science. Perhaps it’s time to ask the parapsychologists. I still have a few questions.

As American virologist Nathan Wolfe expresses this conundrum:

“Don’t assume that what we currently think is out there – is the full story. Go after the dark matter in whatever fields you choose to explore.”

In the aftermath of the public hysteria over climate change and the COVID pandemic, I’m skeptical of anyone who says, “trust the science”.

It’s possible we don’t need to know dark matter’s true identity. The universe has held together reasonably well for billions of years without humanity knowing whether it needs a kind of cosmic Super Glue to remain intact. Mysteries like infinity and eternity are far more perplexing, so much that the best scientists acknowledge their ignorance of these subjects and just move on.

Faith in What Science Can’t Explain

The best reason to accept our current uncertainty about dark matter is to leave room for faith in things science can’t explain. The majesty of the heavens has always inspired humans to seek answers beyond the physical limits of what they can see, touch or otherwise experience. The magic of a song, the beauty of a piece of art, the emotional bond between two people, the serenity of the setting sun over water – these and a million other mysteries need no explanation for them to be real and meaningful.

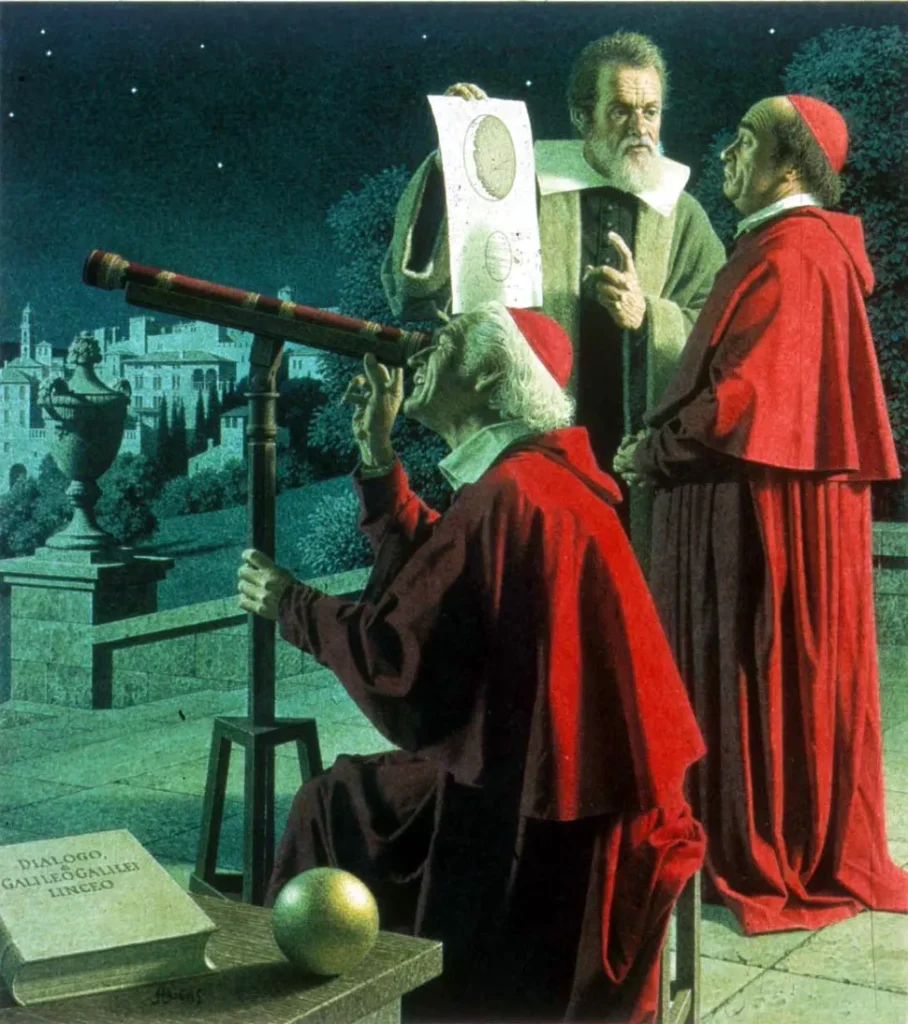

If nothing else, the enigma of dark matter should teach us both humility and perseverance. Famous astronomers such as Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler watched their initial ideas about celestial mechanics get proven wrong. Even Galileo was pressured by the Church to back away from his heliocentric views of the solar system. Later, others learned from these early mistakes and went on to make greater discoveries.

Ultimately, dark matter is a metaphor for the line between man’s curiosity and his hubris. Remember the Tower of Babel.[viii] Intended to reach the heavens and make a name for its builders, the project was abandoned when God confused the builders’ language into many different tongues and scattered them across the whole earth.

Sometimes, recognizing the limits of our understanding is itself the beginning of wisdom.

[i] Perennial Edition (2003)

[ii] Stephen & Lucy Hawking, published posthumously in 2020.

[iii] Primarily gravitational clues.

[iv] Tom Golway, “Entropy Reimagined – Order, Complexity and Transformation”, self-published 2025.

[v] Black holes are gravitational behemoths that dramatically twist time and space. They form when massive stars collapse at the end of their life cycle.

[vi] The world’s largest, high-energy particle collider which lies in a tunnel 17 miles in circumference beneath the border of Switzerland and France.

[vii] NASA’s Fermi telescope is looking for gamma-ray signals produced by the annihilation or decay of WIMPs. As of late 2025, NASA reported that a possible gamma-ray halo in the Milky Way’s center had been identified and could be consistent with WIMP annihilation.

[viii] See Genesis 11.

Be First to Comment