By Peter Pavarini

The practice of scrapbooking began in Great Britain during the mid-19th century when memorabilia such as photographs and printed media became commonplace, and people didn’t know what to do with all of their stuff. Collecting “scraps” (e.g., newspaper cuttings, visiting cards, playbills and pamphlets) initially supplemented and later replaced (to some degree) journaling to preserve one’s personal or family history. Although initially the pastime of affluent women, scrapbooking was quickly adopted by others as a way to record their creative ideas and experiences.

Mark Twain was an avid keeper of scrapbooks, an activity he engaged in mostly on Sundays. As a journalist and a writer, Twain saved reminders of anything he expected to write or speak about in the future. To organize his collection, he invented and patented a self-adhering system of scrapbooking, a business concept some say earned him more money than many of the books he wrote.[i]

Modern Substitutes for Scrapbooks

Like letter-writing and other time-honored traditions dependent upon printed materials, scrapbooking peaked in its popularity during the late 20th century before succumbing to the Digital Revolution.[ii] Today, those who wish to safeguard their memories have many digital means of doing so – most often using their smart phones. By employing online programs and commercial services, people can now artfully compile the detritus of their lives without the bother of glue, sheet protectors or acid-free paper. Regardless of these alternative technologies, there still are many “scrappers” who enjoy scrapbook meets or taking scrapbook cruises[iii] if only for the camaraderie.[iv]

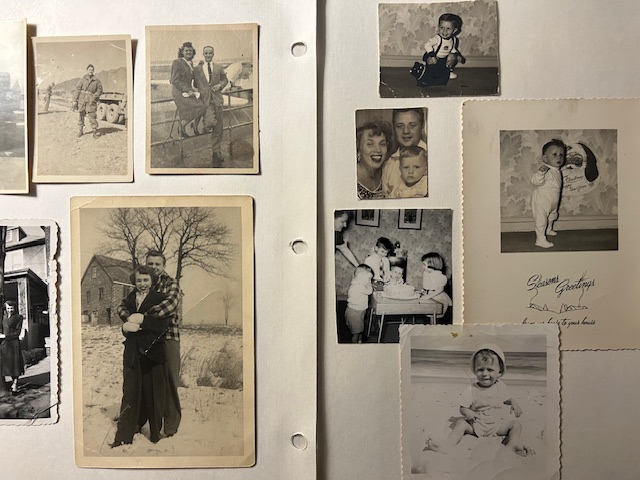

I personally don’t identify as a “scrapper”. However, the recent California wildfires have caused me to wonder what would happen in a disaster to the many boxes of memorabilia I have stored in my attic. Would I feel the same sense of loss experienced by those who recently witnessed a lifetime of memories go up in smoke? Would I be as devastated as those in western North Carolina who watched helplessly as their possessions were washed away by Helene’s floodwaters?[v]

What’s Worth Saving?

As much as I sympathize with these victims, I’m not about to purchase a $5,000 fireproof storage locker or start a new hobby. Admittedly, I did compile a few scrapbooks of childhood memories several years ago, but the process was extremely tedious. When I finished, it didn’t seem as though I had created anything I’d run back into a burning house to save. Also, like others who grew up in the era of Kodak film, I’ve already digitalized countless photographic prints and 35mm slides only to find there’s no digital format that won’t eventually be replaced by newer forms of data storage. Although my wife and I have our “go-bags” ready in case of an emergency, as of now they only contain paper records (like passports and birth certificates) and some cash if the digital financial network crashes.

A Historical Perspective

Humans haven’t always had the ability to save memories outside of their brains. Before the first written languages (i.e., Sumerian pictographs and cuneiform script), early man used various mnemonic methods, such as rhymes, stories and songs[vi], to preserve the information they wanted to keep.

Singing and telling stories weren’t just ways to pass time. In a pre-literate era, these activities were the primary means of passing knowledge and wisdom from one generation to the next. Indeed, without oral storytelling it would have been nearly impossible for indigenous people to preserve their unique traditions and cultures. [vii]

I’ve been reading a series of novels by author Jean M. Auel about Ayla, a Cro-Magnon orphan raised by Neanderthals. Among her many talents, Ayla learns from her adoptive mother the secrets of healing using a cornucopia of herbs and other natural medicines that were available in Ice Age Europe. More intriguing than the imagined sophistication of Neanderthal pharmacology is how the author explains the transfer of this knowledge from one generation to the next. Like the birds which knew how to navigate to warmer climates every winter, Neanderthals passed their wisdom about the healing properties of every plant through inborn memories.

Human Nature Is Communal

Whether or not our species has instinctive memories, humans are unquestionably communal in nature. Advances in neurobiology[viii] show how important social interactions are to maintaining good mental health. Some of this is attributable to how the human brain regulates cognition and emotion. Like a hillside of aspen trees which simultaneously turns yellow on a given day in the fall, we all seem to be interconnected beneath the surface of our individual lives. This community of spirit enables us to share information freely, even across the boundaries of time and space.

And that is why the best way to store one’s memories is through a network of lifelong relationships. If we truly want to preserve what’s most important to us, we can start by making memories every day with those we love – our family members and friends who know us the best.

Therefore, be grateful for the time you have with others. Those precious moments define who you are and imprint your unique qualities on your fellow man. Make them count. And use them to create something that will outlast any flood or fire.

[i] Rebecca Greenfield, “Celebrity Invention: Mark Twain’s Scrapbook”, The Atlantic, November 11, 2010; Ron Powers, Mark Twain: A Life, Free Press (2005) at 435-36.

[ii] Eleanor Levie, “The Once Humble Hobby of Scrapbooking Has Moved On”, New York Time, November 4, 2007; S. Vosmeier, “The Scrapbook in American Life”, Temple University Press (2006).

[iii] Felicia Paik, “A Cruise for Glue and Scissors”, New York Times, November 4, 2007.

[iv] Critics say the $1,000 per month some spend on scrapbooking supplies is a “complete waste of money”. Scrapbooking diehards reply that their hobby is cheaper than therapy.

[v] https://alessandrocamp.com/2024/10/26/lifes-silver-cord/

[vi] Another reason why music seems so central to the human experience. See my previous musings on this subject at https://alessandrocamp.com/2023/11/15/singing-with-friends/

[vii] Chad Valdez, “The Importance of Indigenous Oral Traditional Storytelling”, www.culturalsurvival.org, March 19, 2024.

[viii] Simon N. Young, “The Neurobiology of Human Social Behavior: An Important but Neglected Topic”, Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience, September 2008.

Be First to Comment